I recently completed an implementation of the Raft consensus algorithm! It is part of the homework of the online version of MIT course 6.824. It took me 10 months on and off, mostly off.

The algorithm itself is simple and understandable, as promised by the paper. I'd like to summarize my implementation, and share my experience as an engineer implementing it. I wholeheartedly trust the researchers on its correctness. The programming language I used, as required by 6.824, is Go.

Raft

Raft stores a replicated log and allows users to add new log entries. Once a log entry is committed, it will stay in the committed state, and survive power outages, server reboots and network failures.

In practice, Raft keeps the log distributed between a set of servers. One of the servers is elected as the leader, and the rest are followers. The leader is responsible for serving external users, and keeping followers up-to-date on the logs. When the leader dies, a follower can turn into the leader and keep the system running.

Core States

In the implementation, a list of core states are maintained on each server. The states include the current leader, the log entries, the committed log entries, the last term and last vote, the time to start an election, and other logistic information. On each server, the states are guarded by a global lock. Details are here.

The states on each server are synchronized via two RPCs, AppendEntries and RequestVote. We'll discuss those shortly. RPCs (remote procedure calls) are requests and responses sent and received over the network. It is different from function calls and inter-process communication, in the sense that the latency is higher and RPCs could fail arbitrarily because of I/O.

Looking back at my implementation, I divided Raft into 5 components.

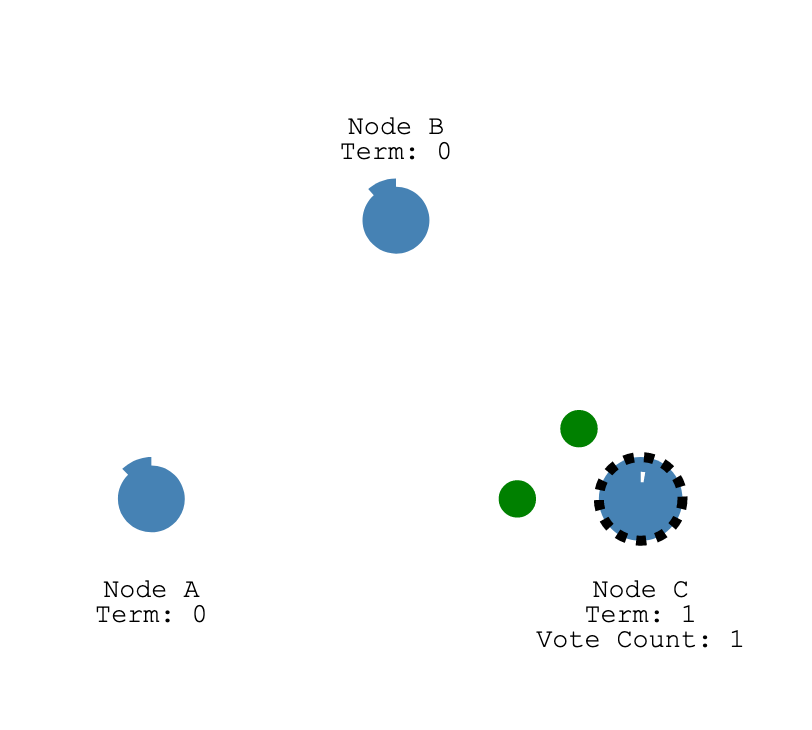

Election and Voting

Responsible for electing a leader to run the system. Arguably the most important part of Raft.

An election is triggered by a timer. When a follower has not heard from a leader for some time, it starts an election. The follower sends one RequestVote RPC to each of the peers, asking for a vote. If it collects enough votes before someone else starts a new term, then it becomes the new leader. To avoid unnecessary leader changes, the timer will be reset every time a follower hears from the current leader.

Asynchronous operations can lead to many pitfalls. Firstly, If an election is triggered by a timer, we could have a second election triggered when the first is still running. In my implementation, I made an effort to end the prior election before starting a new one. This reduces the noise in the log and simplifies the states that must be considered. It is still possible to code it in a way in which each election dies naturally, though.

Secondly, latency matters in an unreliable network. A candidate should count votes ASAP when it receives responses from peers, and a newly-elected leader must notify its peers ASAP that it has collected enough votes. Using a channel in those scenarios can introduce significant delays, to the point that elections could not be reliably completed within the usual limit of 150ms ~ 250ms.

Thirdly, when the system is shut down, an election should be ended as well. Hanging elections confuses peers, and more importantly, also confuses the testing framework of 6.824 that evaluates my implementation.

Heartbeats

To ensure that followers know the leader is still alive and functioning, the current leader sends heartbeats to followers. Heartbeats keep the system stable. Followers will not attempt to become a leader while they receive heartbeats. Heartbeats are triggered by the heartbeat timer, which should expire faster than any followers' election timer. Otherwise those followers will attempt to run an election before the leader sends out the heartbeat.

In my implementation, one "daemon" goroutine is created for each peer, with its own periodical timer. The advantage of this design is that peers are isolated from each other, so that one lagging peer won't interfere with other peers.

The leader also sends an immediate round of heartbeats after it has won an election. This round of RPCs is implemented as a special case. It does not even share code with the periodical version.

The Raft paper did not design a specific type of RPC for heartbeats. Instead, it uses an AppendEntries RPC with no entries to append. The original purpose of AppendEntries is to sync log entries.

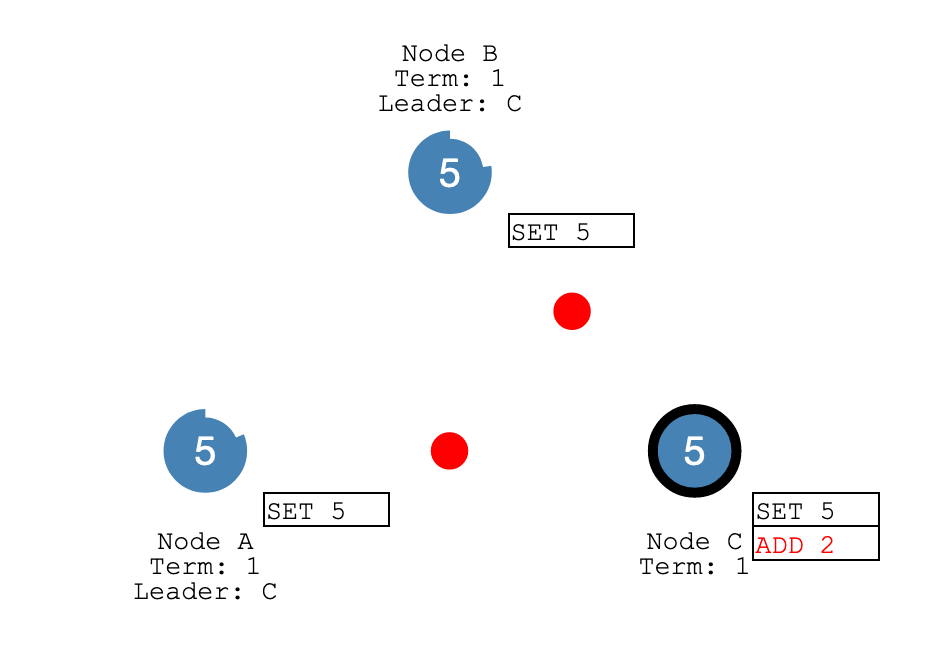

Log Entry Syncing

The leader is responsible for keeping all followers on the same page, by sending out AppendEntries RPCs.

Unlike heartbeats, log entry syncing is (mainly) triggered by events. Whenever a new log entry is added by a client, the leader needs to replicate it to followers. When things run smoothly, a majority of the followers accept the new log entry. We can then call that entry "committed". However, because of server crashes and network failures, sometimes followers disagree with the leader. The leader needs to go back in the entry log, find the latest entry that they still agree on ("common ground"), and overwrite all entries after that.

Finding "common ground" is hard. In my implementation this is a recursive call to the same tryAppendEntries function. The function sends an AppendEntries RPC and collects the response. In case of a disagreement, it backtracks up the log entry list exponentially. First it goes back 1 entry, then X entries, then X^2 entries and so on. The recursion will not go too deep because of the aggressive "backtrack" behavior. This does mean a lot of the entries will be sent over the network repeatedly, which is less efficient.

The aggressive backtrack behavior is mainly designed for the limits set by the testing framework. In some extreme tests, an RPC can be delayed by as much as 25ms, or be dropped randomly, or never return. The network is heavily clogged. An election is bound to start in about 150ms after a leader has won, when heartbeat RPCs fail and one of the election timers triggers. That means the current leader only has ~6 RPCs (150ms / 25ms) to communicate with each peer, fewer if some RPCs are randomly lost in the network. The "backtrack" function really needs to go from 1000 to 0 in less than 6 calls. I imagine it will be tuned very differently, if the 95 percentile RPC latency to the same cell is less than 5ms.

AppendEntries RPC are so important that they must also be monitored by a timer. In some RPC libraries, an RPC can fail with a timeout error, and the timeout can be set by the caller. Unfortunately labrpc.go that comes with 6.824 does not provide such a nice feature. I implemented the timer as part of the Heartbeat component, which checks the status of log sync before sending out heartbeats. If logs are not in sync, tryAppendEntries RPCs are triggered instead of heartbeats.

Like heartbeats, each peer should have its own 'daemon' goroutine that is in charge of log syncing. The heartbeat daemon could share the same goroutine with it. However I did not find a way to wait for both a ticking timer and an event channel at the same time. Let me know if you know how to do that! Another thing is that my obsolete "all peers bundled together" system worked good enough. I did not bother to upgrade.

Internal RPC Serving

We talked about how to send AppendEntries and RequestVote RPCs. But how are those RPCs answered?

The Raft protocol is designed in a way that the answer can be given just by looking at a snapshot of the core states of the receiving peer. There is no waiting required, except for grabbing the lock local to each peer. The only twist is that receiving those two RPC calls can result in a change of core states. If other components are designed to expect state change at any time, there is nothing to worry about.

External RPC Serving

Only the leader serves external clients. Each peer should forward "start a new log entry" requests to the current leader. This part is not required by 6.824 and not implemented.

In reality, clients should communicate with the system via RPCs. Just like internal RPC serving, the implementation should be straightforward.

The 6.824 testing framework also requires each peer to send a notification via a given Go channel, when a log entry is committed. I don't think this requirement applies to a real world scenario. This part is implemented as one daemon goroutine on each peer. It is made asynchronous because it communicates with external systems which might be arbitrarily slow. No RPC is involved.

Conclusion

Coding is fun. Writing asynchronous applications is fun. Raft is fun.

That concludes the summary. Stay tuned for my thoughts and comments!